Ultrasound-Guided INTRAPEC Injection for Breast Surgery: A Novel Solution for Surgical Field Improvement During Electrocautery and Implantation and for Postoperative Pain and Muscle Spasm Reduction for Breast Surgery

Jonathan P. Kline, MSNA, CRNA

Affiliation:

Director of Education at Twin Oaks Anesthesia

Abstract:

This article introduces a novel ultrasound-guided injection called the INTRAPEC technique as a solution to the specific problem of intraoperative pectoral major muscle spasm during electrocautery and manipulation. The technique is a cost- effective, nonparenteral method for improving the surgical field during pectoral major isolation and subsequent implant placement. The technique may have added benefits such as a significant reduction in surgical complexity causing trauma and bleeding and significant reductions in postoperative pain and muscle spasm.

Introduction:

Regional anesthetic techniques for plastic surgery present a particular set of challenges for anesthesia providers. Two recognized issues are the complex, wide, and sometimes not well described pain generators from the extensive areas involved with plastics procedures and the risk of LAST (local anesthetic systemic toxicity). The latter is arguably the result of additional doses of local anesthetics administered by surgeons in the form of tumescent fluid. For the past several years, PECS 1 and 2 blocks targeting the pectoral musculature have gained popularity as effective, opioid-sparing, multimodal pain- reducing techniques for analgesia for breast and anterior trunk surgical pain. The techniques continue to gain momentum

for their ease of placement and safety, compared with prior techniques such as thoracic epidural and paravertebral blocks. In theory, the PECS 1 technique, involving ultrasound-guided placement of a local anesthetic between the pectoralis major and minor, should denervate the muscle group, reducing spasm and irritation caused by surgical manipulation and subsequent placement of expanders or implants. However, during pocket creation, these muscle planes are violated and may cause the complete release of the carefully placed local anesthetic, dramatically altering its expected duration of action.

Like all other nerve block techniques, the PECS 1 block does not cause intramuscular flaccidity during electrical dissection (electrocautery). This leakage of the local anesthetic away from the target nerves will ultimately reduce postoperative pain and spasm control. This spasm of the muscle has been a source of contention between our surgical colleagues and anesthesia since surgery with muscle relaxants began. The spasm and muscle contraction of the pectoralis major during the dissections and space creation for implantation remains problematic, despite denervation occurring at the myoneural junction through the PECS 1 technique.

It is theorized that an ultrasound-guided injection of the pectoralis major muscle, done well ahead of the surgical dissection and space creation, might improve pectoralis muscle rigidity and spasm and potentially lessen trauma and bleeding during surgical techniques involving implantation. This may improve surgical field conditions during this phase of surgery and potentially reduce pain, spasm, and any need for intravenous muscle relaxants. It is also theorized that this technique may improve postoperative pain outcomes as a direct result of reduced muscle confrontation leading to trauma and spasm that occur during surgery.

Background:

Intramuscular injections for the relief of pain and spasm are

not a new concept. Pain management providers use a range of such techniques for a variety of ailments. Examples include intramuscular injections for the relief of piriformis syndrome, iliotibial band release, and various posterior trunk musculature injections for trigger point treatment. These injections share commonalities that are all relieved by the injection of local anesthetic. Additionally, they all involve elements of pain and spasm reduction, and the need for analgesic medicines. It is

also possible that the evolution of chronic pain following breast reconstruction may originate from spasm and irritation of the pectoral compartment containing the medial and lateral pectoral nerves by the implant itself. Surgical denervation of neuroma secondary to this pain syndrome is a common element for certain breast reconstruction procedures, sacrificing sensation in most cases and function in others. In many cases, this intramuscular injection can release spasm and pain. It is suggested that infiltration of the pectoralis major muscle (INTRAPEC)

can reduce the spasm of the pectoral major muscle during electrocautery and potentially into the recovery phase.

Review of the Literature:

A PubMed (National Library of Medicine) search using the keyword “pectoral muscle injection” was performed and yielded several relevant articles. Many of the articles suggested using the PECS blocks for acute and chronic pain treatment following breast surgery. Interestingly, several articles reported postoperative treatment of existing pectoralis major muscle spasms with intramuscular injections of botulinum toxin type A (Botox-A). However, we found no articles in which a preoperative ultrasound-guided intramuscular injection was used directly for the purpose of spasm reduction during surgery or to reduce postoperative pain.

In 2011 O’Donnell and colleagues successfully treated a patient with persistent post-breast-surgery pectoral muscle spasms with an intramuscular injection.1 This is one example of use of botulinum toxin type A (Botox-A) treatment for pectoral muscle conditions related to surgery suggesting proof of concept for an intramuscular injection. Govshievich and colleagues reported a case presentation involving, again, postoperative pectoral muscle pain after breast surgery.2 In that case, the authors used the novel PECS 1 block as a diagnostic measure to more accurately identify the pain generator for this persistent pain. The PECS 1 block was done using ultrasound with symptom relief. Shin and colleagues described combination intramuscular injections of

the subscapularis and pectoralis major muscles for the relief of postmastectomy shoulder pain.3 They found that postmastectomy patients benefitted from this combination technique. Their technique described an intramuscular injection performed under ultrasound. However, again, it targeted postoperative treatment options for these persistent symptomatic patients. We found

no mention of preoperative placement.3 In 2014 Leiman and colleagues reported on the early use of liposomal bupivacaine (Exparel) in an ultrasound-guided PECS 1 block for the management of postoperative pain after breast surgery.4 The technique involved the placement of a local anesthetic in the fascial plane between the pectoralis major and minor targeting the medial and lateral pectoral nerves. However, note that at the time of this writing, liposomal bupivacaine (Exparel) is currently cleared only for infiltration type regional blocks but now includes interscalene “nerve blocks”. This is an important distinction specific to the PECs 1 approach because although targeting the medial and lateral pectoral nerves, it's accomplished by an infiltration of local anesthetic between the fascial planes created by the pectoral major and minor muscles. Despite this limitation in the US, there are many articles that have described Exparel’s safe and effective use in nerve blocks, such as the median and lateral pectoral nerve blocks in the PECs 1 approach. Finally, Trignano et al reported on the use of an injection of the pectoral muscle, using botulinum toxin type A (Botox-A), for relief of pectoral muscle spasms in 2011.5 Although the team reported favorable results of the intervention, the pectoral muscle was used as a flap for head and neck surgery, which is not exactly in league with this topic. However, mention of the technique is warranted to support proof of concept.

Patient Presentation:

The surgeon and patient agreed to this technique being performed in the office-based outpatient surgical center. The patient was

a 20-year-old woman, American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) category 1, who was void of any comorbidities or prescribed home medications. She denied any prior surgical exposure, specifically breast procedures. She denied any allergies or illicit drug or alcohol use and was void of any physical or mental disabilities. The only discomfort she stated before the procedure was menstrual pain, which she characterized as moderate to severe. She presented to the office-based surgery suite with desire for bilateral breast augmentation. She was informed of the anesthesia plan involving general anesthesia with laryngeal mask airway, in combination with PECS 1, PECS 2, and the additional technique we termed INTRAPEC injection. She demonstrated understanding of the risks and benefits and agreed to proceed.

Technique:

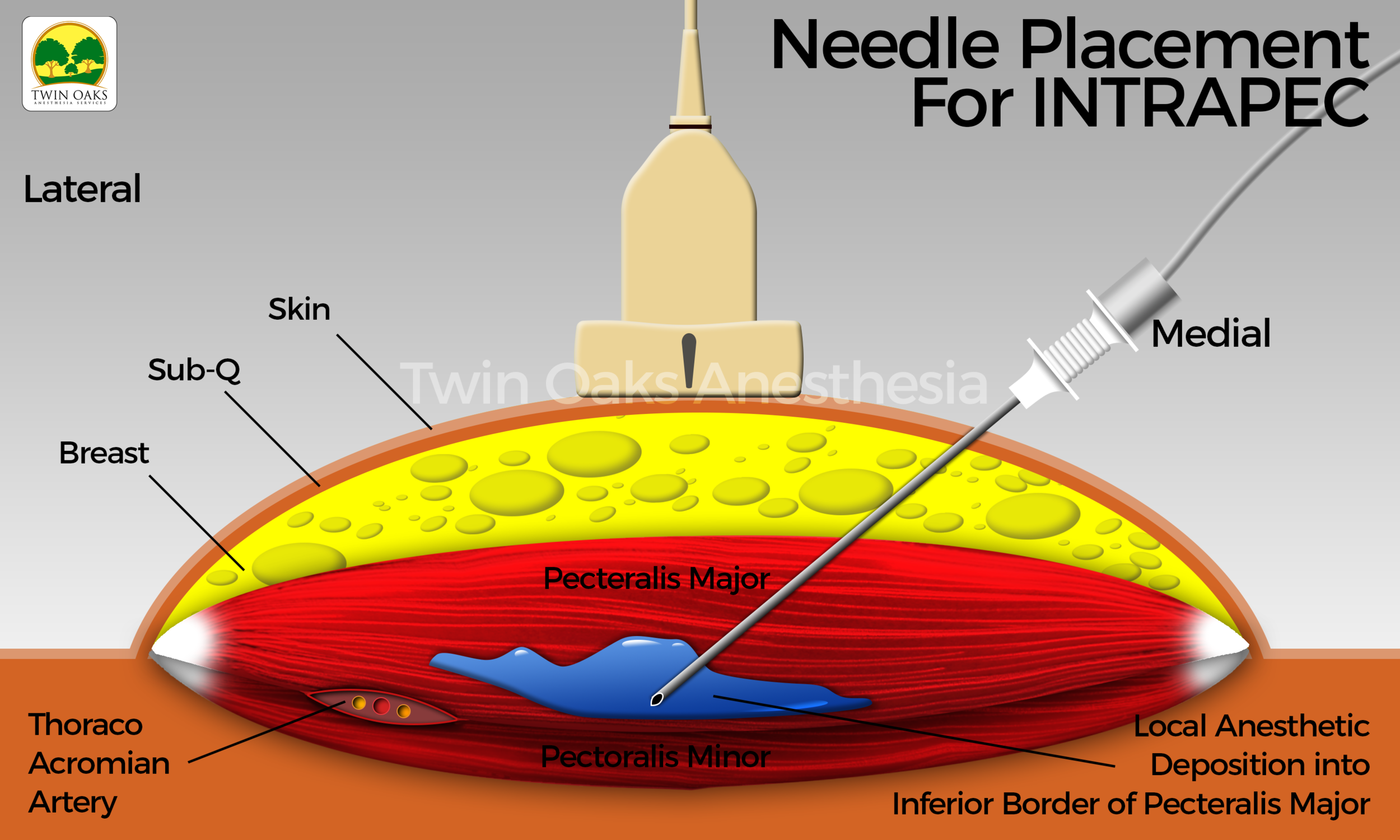

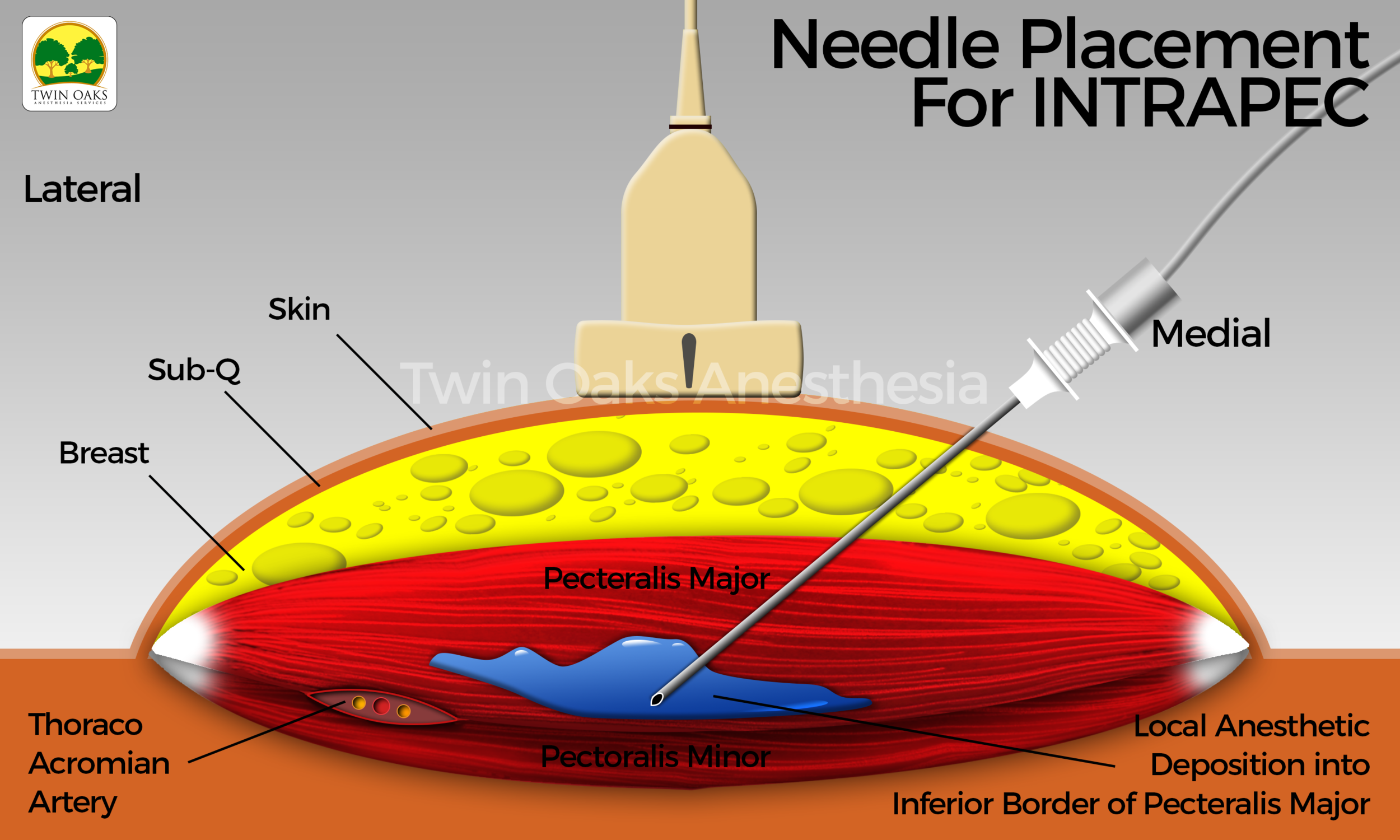

Following explanation of the procedure to the patient, and prior approval from the surgeon, the patient positioned herself on the operating room table. An institutional time out was performed, and monitors and oxygen were applied. The patient’s baseline vital signs were recorded, preoxygenation was employed, and general anesthesia with placement of a laryngeal mask airway were easily performed. The skin was prepped with sterile chlorhexidine, and sterile single-use gel was applied to the suspected areas of interest. A probe cover (SaferSonic, Highland Park, IL) was applied and the ultrasound image optimized. The ultrasound- guided INTRAPEC technique was accomplished with the use of a high-frequency linear transducer (Terason L15 paired with a Terason 3300 ultrasound system, Burlington, MA). The probe was positioned transverse over the anterior chest below the clavicle, beginning at the origin of the pectoral major medially, similar to that described by Blanco for the PECS 1 technique. The inferior and posterior border was identified sonographically and was specifically targeted. An 80-mm, 22G echogenic needle (Pajunk, Germany) was introduced from medial to lateral into this discrete muscle region, following placement of the PECS 1 block. The goal of the injection was to concentrate local anesthetic to the aponeurosis of this anterior and inferior border of the pectoral major muscle. Doppler mode was engaged to assist in the location of the vasculature in the region of interest. Following aspiration and complete expulsion of all air from the needle, connective tubing, and syringe, a mixture of lidocaine 2% and ropivacaine 0.5% was infiltrated. A total volume of 15 mL per muscle was placed. The injection was safely performed in a medial to lateral fashion, promoting safety by directing the needle away from the deeper thoracic structures.

See Figure 1 for an actual patient ultrasound image of the INTRAPEC procedure. The Figure shows the right-sided INTRAPEC technique. The needle is correctly placed into the anterior/inferior border of the pectoral major muscle.

Figure 2 shows the ultrasound-guided INTRAPEC injection being performed. Figure 3 is an illustration of an ultrasound- guided INTRAPEC injection.

Figure 3 is an illustration of an Ultrasound-Guided INTRAPEC injection.

Results:

We report 2 aspects of this technique, the results from the surgeon’s experience during electrocautery and implantation, and the patient's experience of pain after surgery. The surgeon stated that the creation of a surgical pocket was considerably easier and was accomplished without unpredictable muscle contraction during periods of electrocautery or manipulation via the lighted retractor. Additionally, the surgeon stated that the surgical field was more easily maintained free of muscle spasm and bleeding. This seemed to promote ease of implant placement. The surgeon reported favorable results and was agreeable to reproducing the technique on future cases. The patient reported only “pressure” from the surgical procedure; however, she complained of intense menstrual pain. She also stated that she had more pressure-like discomfort to the right breast than to the left. It was clear that the incisional and surgical region was not causing the patient discomfort. However, she was given 1 oxycodone orally, per the surgical postoperative regimen, to ease her abdominal discomfort before her ride home. In the immediate post-anesthesia care unit area, and on postoperative day one, she had no pectoral muscle spasms and needed no pain medication for her surgical regions.

Discussion:

We made observations during the placement of the INTRAPEC injection. First, the infiltration can be easily accomplished immediately following the PECS 1 block, as the needle is in nearly the correct position at that time. This suggests ease of placement and a small learning curve for those already using the PECS 1 block. During the surgical procedure, specifically, during the dissection and pocket creation of the pectoral major muscle, extremely little muscle contraction was seen during electrocautery. When asked how the pocket creation was compared with similar patients with similar presentations, the surgeon stated, “it was like the muscle was completely paralyzed.”This notion alone, that the problem of muscle spasm during electrocautery could be significantly improved with the simple addition of local anesthetic represents a bold step forward for both anesthesia providers and surgeons. This opens the door to more ultrasound-guided regional injections for a variety of purposes, potentially making optimal surgical fields less reliant on intravenous muscle relaxants.

We recognize some limitations and drawbacks from the addition of the ultrasound-guided INTRAPEC injection technique. The first element is the careful observation of the total dose of local anesthetic and potential of LAST. This element should be carefully considered because it is unique to this patient population and plastic surgery regarding the addition of tumescent fluid.

The addition of tumescent fluid commonly incorporates larger volumes of local anesthetics as a part of the surgical regimen. Because the INTRAPEC technique is likely to be added to existing techniques such as the PECS 1 and 2 blocks, or other truncal techniques, this total dose should be carefully considered. Muscle relaxation facilitated by local anesthetics is likely associated with a high concentration of local anesthetics; thus, careful consideration of total dose is advised.

The potential for disastrous needle misadventure should also be mentioned. In novice hands, this technique may pose significant complications to the patient in the form of structure violation. This can lead to conditions such as cardiac tamponade, pneumothorax, or large vessel puncture, such as to the subclavian artery or vein. However, a more likely scenario might be puncture of a smaller vessel known to be in this region, such as the thoracoacromial artery. This artery is reliably found on ultrasound between the pectoralis major and minor during the PECS 1 block.

It is possible for the surgeon to simply inject the inferior anterior border during dissection or under direct visualization following exposure. However, the delayed onset of the effect of this injection on reducing spasm and reactivity to electrocautery makes early infiltration (such as preoperative or following induction) sensible. It is likely that by the time the patient is ready for surgical dissection, the effects of the INTRAPEC technique will have peaked. In addition, the safety of ultrasound guidance for vessel identification and needle guidance accuracy will be lost with a direct vision technique.

A postoperative injection using the same technique could be suggested as well. However, preoperative placement without an implant yields natural muscular architecture, making the sonographic landscape easier to navigate. The incidental placement or trapping of air anywhere in the surgical field would have deleterious effects on the acquisition of ultrasound imaging. Last, a fresh implant and carefully closed plastic surgery incision should be cautiously negotiated with further blocks. Accidental opening of these incisions for the plastics patient can lead to further closure revision, undesirable scar formation, infection, implant violation, or other avoidable complications. This can be avoided by simply placing the INTRAPEC injection before incision and plane rearrangement.

Conclusions:

The ultrasound-guided INTRAPEC injection appears to enhance surgical field compliance during breast implantation for reconstruction and augmentation. The technique suggests that injecting the muscle itself, at the anterior/inferior border near

the aponeurosis, may lead to less spasm, incidental trauma and bleeding, and reduced muscle confrontation to the surgeon. The placement of the injection is relatively simple and straightforward and can easily be accomplished in conjunction with a PECS 1 block. The technique is further made safer by the addition of ultrasound guidance. This seems evident by not only improved accuracy from an in-plane needle guidance, but avoidance of significant structures, arguably only centimeters away from the target zone. Further safety is offered during the placement by the advantage of color Doppler viewing to assist in identification of vasculature in the infiltration zone. We look forward to and recognize the need for more formalized studies investigating this simple technique of surgical field improvement and potential pain reduction for surgical patients undergoing breast expansion or augmentation. By its very nature of being both a novel technique and a single case study, we recognize that although successfully demonstrating proof of concept, this technique is in its infancy, and clearly more studies are required to validate its use.

REFERENCES

1. O’Donnell CJ. Pectoral muscle spasms after mastectomy successfully treated with botulinum toxin injections. PM R. 2011 Aug;3(8):781-2. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2011.02.023

2. Govshievich A, Kirkham K, Brull R, Brown MH. Novel approach to intractable pectoralis major muscle spasms following submuscular expander-implant breast reconstruction. Plast Surg Case Studies. 2015;1(3):68-70.

3. Shin HJ, Shin JC, Kim WS, Chang WH, Lee SC. Application of ultrasound-guided trigger point injection for myofascial trigger points in the subscapularis and pectoralis muscles to post-mastectomy patients: a pilot study. Yonsei Med J.2014;55(3):792-799. https://doi.org/10.3349/ymj.2014.55.3.792

4. Leiman D, Barlow M, Carpin K, Piña EM, Casso D. Medial and lateral pectoral nerve block with liposomal bupivacaine for the management of postsurgical pain after submuscular breast augmentation. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2014;2(12):e282. https://doi.org/10.1097/GOX.0000000000000253

5. Trignano E, Dessy LA, Fallico N, et al. Treatment of pectoralis major flap myospasms with botulinum toxin type A in head and neck reconstruction. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2012;65(2):e23-e28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjps.2011.10.002